- Home

- Investor Centre

- Sustainability

- Talent

- News

- Insights

- TH!NK

- Corporate Governance

- Company Profile

- Board of Directors

- Community

- MCB Offices

Contact Info

China’s shift from lender to collector leaves developing economies exposed

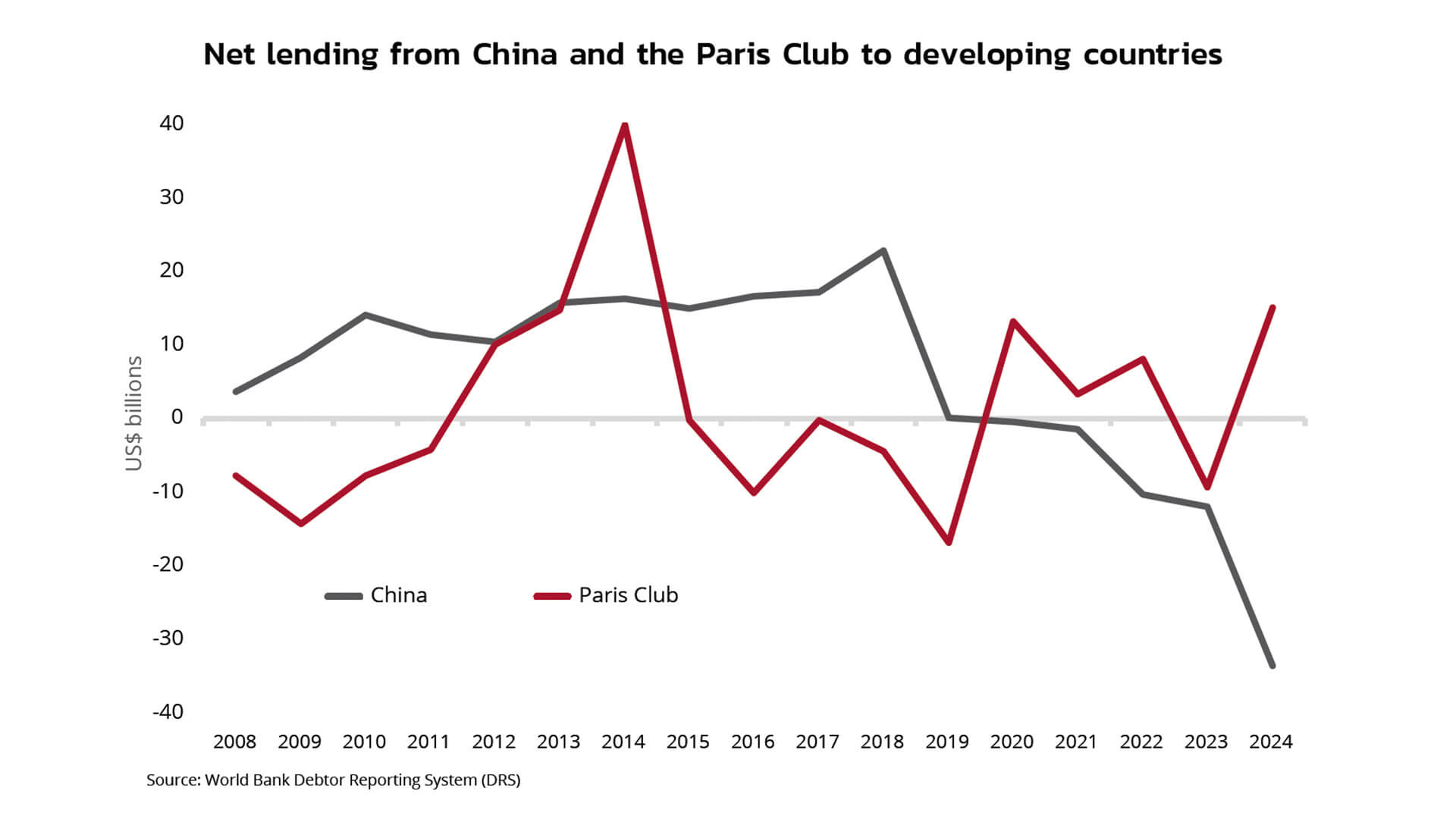

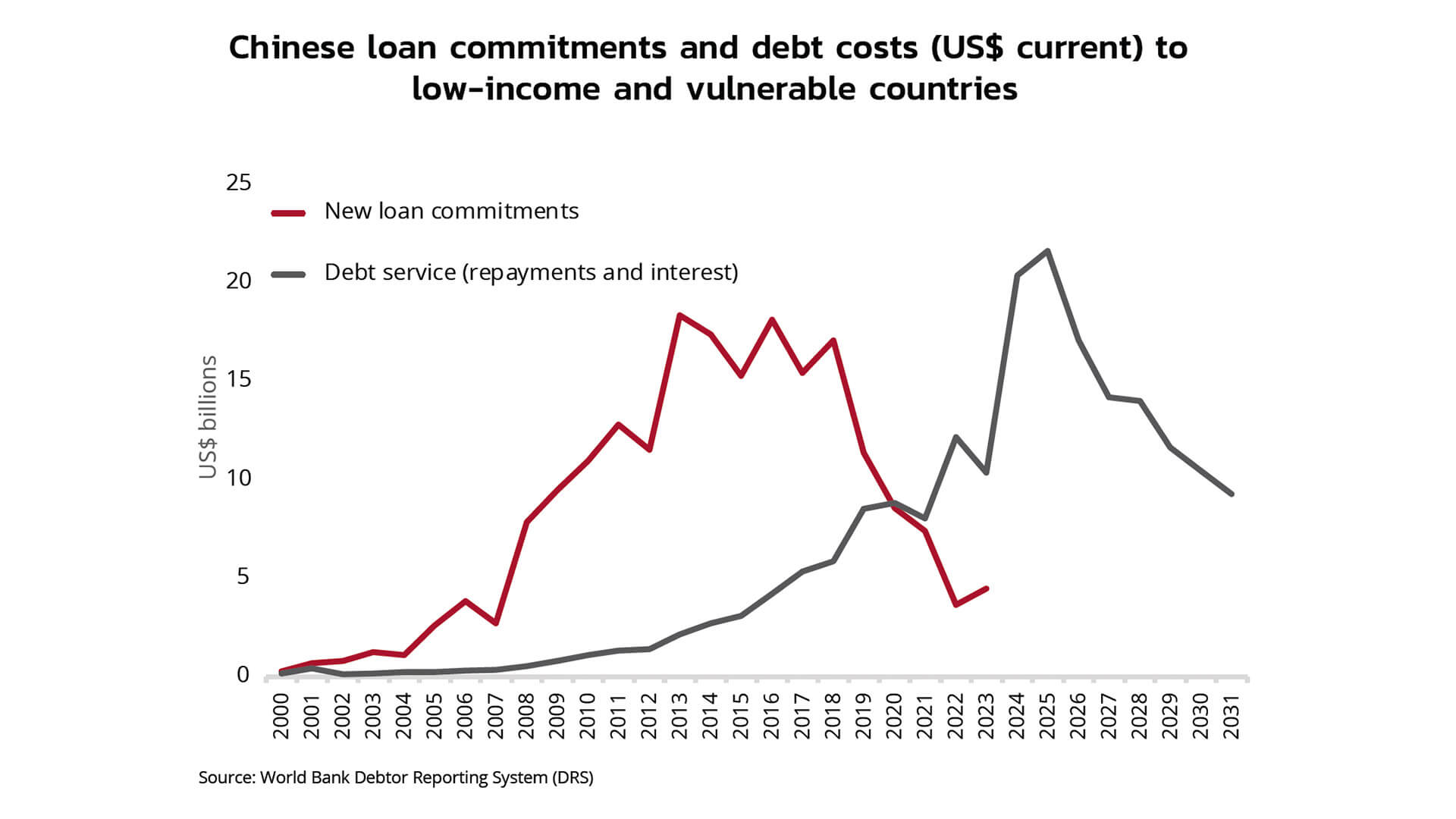

Over the past decade, China’s role in developing-country finance has shifted dramatically. Once the leading lender to low-income nations, especially through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China is now the largest recipient of debt service payments from these same countries. While Chinese lending peaked in 2013 at about $18 billion, it has since declined sharply. In contrast, debt repayments by developing economies to China reached $33.6 billion in 2024, more than twice the amount paid to traditional Paris Club lenders, according to World Bank data. Payments from low-income and vulnerable nations are projected to hit a record $22 billion in 2025, intensifying fiscal pressures and limiting economic growth.

This marks a key turning point as many countries are now repaying China more than they receive in new loans. During recent crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s financial support dwindled while Western aid increased. Chinese loan commitments have dropped to levels last seen in 2007/08, even as China’s share of global debt service has soared. Over 50 nations now pay more to Chinese lenders than to all Paris Club creditors combined. A 2023 report from Australia’s Lowy Institute revealed that over a quarter of developing-country external debt is owed to China, which now holds more than half of all bilateral debt in the poorest nations.

Despite its central role, China has shown limited willingness to engage in broad debt relief. Though it has participated in a few restructurings, its cooperation in multilateral efforts like the G20’s Common Framework has been limited. Domestically, Beijing faces its own economic pressures and needs to recover loans issued by state-owned banks, which further restricts its flexibility. This leaves many fragile economies exposed, forced to reduce critical spending on health, education, and climate programs to service mounting debt.

Still, China continues to lend selectively to countries it considers strategically important. These include nearby nations like Pakistan and Kazakhstan, and resource-rich states such as Argentina, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Lending also functions as a diplomatic tool, with China often rewarding countries that shift allegiances to Beijing. This aligns with its broader geopolitical rivalry with the United States, which is also increasing its strategic engagement in regions like the DRC to secure access to rare earth minerals.

As official lending slows, Chinese private firms, often with indirect state backing, are expanding investments in renewable energy and electric vehicles across BRI nations. Projects in solar, wind, and EVs are proliferating in Asia and Africa, allowing China to maintain its global influence and leadership in clean tech even as state development finance contracts.

Ultimately, rising debt repayments to China, coupled with declining Western aid, are straining development in many countries. Without greater debt relief efforts from Beijing or renewed financial leadership from the West, these nations risk deeper debt crises, political instability, and prolonged stagnation, underscoring China’s growing power and responsibility in shaping the future of global development finance.

Subscribe to our Email Alerts

Stay up-to-date with our latest releases delivered straight to your inbox.

Contact

Don't hesitate to contact us for additional info

Email alerts

Keep abreast of our financial updates.